Economics can be boring as hell. Even I wasn’t really passionate while studying it, only a few years later did I get a real taste for it. Teaching a class titled “Introduction to economics” to law students in their first year of bachelor degree has encouraged me to find alternative approaches to the topic, trying to hook an audience for whom economics is usually not of much interest.

There are many reasons why economics can sound boring :

- A disproportionate use of mathematics. I will definitely expand on that later, it is a methodological controversy to which I dedicated a substantial paragraph in the lesson.

- The use of technical jargon without clear and precise definitions of said terms, or failure to give a synonym in everyday language. This is a major problem when such crucial words as “value”, “inflation” or “money” actually have several meanings, even within the realm of economics. In my experience, this makes highly qualified economists have surreal conversations in seminars where they seem to talk past each other, unbeknownst to them.

- The existence of major and durable disagreements among different schools of thought. Witnessing such controversies in a field that has made so much efforts to appear rigorous and “scientific” is puzzling for many observers, and those who were initially trained in “hard sciences” like (especially maths and physics) tend to cast doubt on the validity of academic research in economics.

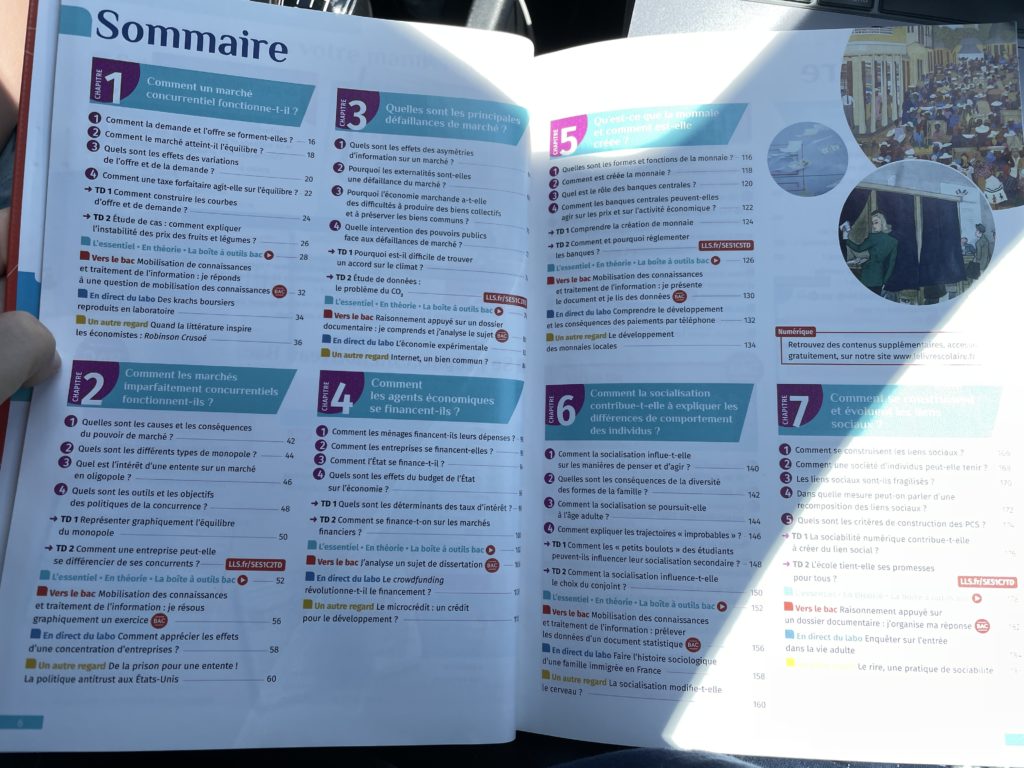

But today I wanted to focus on a fourth reason : the failure to properly, interestingly and deeply explain what is economics, what it can and can’t explain or predict, why people should be eager to study it, and just how important economics have always been in the history of mankind, not just in the past few centuries but since the origins of civilization. You can already see it in the summary of this textbook of economics and social sciences for high school students :

As french readers will notice, the first chapter explains how competitive markets work. The next one how markets work in the presence of imperfect competition. The third one deals with markets failures (definitely the highlight for most french teachers…). The fourth chapter studies financing in/of the economy, and the last economic chapter tackles the subject of money.

First, I have to admit this is a good textbook in terms of structure. Besides the usual left-leaning bias (so ingrained among french teachers that most wouldn’t even call it a bias), there are clear explanations, well-chosen examples, frequent references to the history of thought, and even brief summaries of current research (they call these sections “live from the lab”). But to me, something is missing. I know from experience that many students will learn whatever you teach them without too much discussion, and more importantly without asking some obvious and yet important questions. This could be the result of a lack of curiosity, excessive deference to their teachers, or a fear of sounding stupid in front of others. In any case, I tried to figure out some of those potential questions, mainly by trying to get in the head of your stereotypical passive student whose only purpose is to make sure he’ll get a good enough grade.

So for my own introduction chapter (technically an introduction to the introduction to economics !), I chose the title “What is the point of studying economics ?”. I then go on to explain why economics concerns us all in almost every hour of our lives – whether we like it or not – and how crucial it is to a better understanding of most other social sciences : history, sociology, political science, international relations, etc. As I also suspect that many law students do not immediately grasp the importance of economics in the context of their studies, I try to remind them how pointless and even harmful laws can become when directed against fundamental economic principles. I also mention how an economic view can serve lawmakers, as demonstrated by the fascinating field of “law and economics”. I also remind them of all the reasons why people may – understandably – doubt the truth and relevance of what economists have to say. By the way, there is no such thing as a “truth” or a “fact” when it comes to economic issues, at least as they are portrayed in the media. Concepts such as unemployment, prosperity, general price level, etc. can be defined, measured and presented in many ways, and even with the most accurate of definitions you will eventually struggle with incomplete or imprecise data. In short, I try to stress how humble economists should be about their own science. However, even the most basic and agreed upon results of economics are challenged or even outright ignored by politicians and voters alike, on a daily basis. So even this very imperfect economic science (which a feature of any social science, not a bug) could immensely help our societies if only more people were willing to understand them.

Another thing I like to emphasize is just how political economics can become for those willing to make them so. It’s okay to have opinions, values and beliefs, I don’t hide my strong belief in the economic and philosophical virtues of individualism and free-market as a base for society. But even the most militant of students won’t gain anything from refusing to observe how the world works. Even when you think it should work differently and want to implement change, your best bet is to first leave your morals aside and try to understand why the world is organized as it is and why others before you have succeeded or failed to change it. For example, one should never deny the function of the price system and its necessary fluctuations. That being said, prices can still be twisted in a certain direction or even temporarily ignored, but the consequences should always be clear and understood by everyone. As it turns out, only a humble student of market prices can predict some of those consequences. and trade-offs.

Finally, here are a few questions that I came up with and listed down for my students, as a way to provide them with concrete examples of how economics can cast a new light on matters which would otherwise seem illogical or unacceptable :

Why is the freedom to lower wages in any given industry as important to overall prosperity as the freedom to raise them ?

Why do the most indebted countries face the highest interest rates when they borrow money, while they are the ones who need it the most ?

How is it that an increase in productivity in one country automatically enriches its international trading partners, while trade is so often presented as a competition between countries ?

How could the Spanish Empire be eventually impoverished by the arrival of hundreds of tons of gold from the Americas ?

Why do the majority of resource-rich countries suffer from delayed economic development and high inequality ?

Let me know what you think in the comments section, and write something if you’d like to read my full “introduction to the introduction” to economics.